Two thousand years ago, it was the capital of a powerful trading empire. Now archaeologists are piecing together a more complete picture of Jordan’s compelling rock city

“Donkey, horse or camel?” The question from my Bedouin guide reminds me of a rental car agent asking, “Economy, full-size or SUV?” I choose economy, and we canter on our donkeys through the steep valleys that surround Petra, in Jordan, as the rock changes from red to ocher to orange and back to red. Two millennia ago our now deserted track was a well-engineered caravan route, bustling with itinerant traders on foot, Roman soldiers on horseback and rich merchants on camels.

Directly ahead is a sheer cliff lined with elegant carvings reminiscent of Greek and Roman temples, a surreal vision in this remote mountain valley surrounded by desert. This is the back door to Petra, whose very name means rock in Greek. In its heyday, which began in the first century B.C. and lasted for about 400 years, Petra was one of the world’s wealthiest, most eclectic and most remarkable cities. That was when the Nabatean people carved the most impressive of their monumental structures directly into the soft red stone. The facades were all that remained when 19th-century travelers arrived here and concluded that Petra was an eerie and puzzling city of tombs.

Now, however, archaeologists are discovering that ancient Petra was a sprawling city of lush gardens and pleasant fountains, enormous temples and luxurious Roman-style villas. An ingenious water supply system allowed Petrans not just to drink and bathe, but to grow wheat, cultivate fruit, make wine and stroll in the shade of tall trees. During the centuries just before and after Christ, Petra was the Middle East’s premier emporium, a magnet for caravans traveling the roads from Egypt, Arabia and the Levant. And scholars now know that Petra thrived for nearly 1,000 years, far longer than previously suspected.

Our donkeys slow as we approach Petra’s largest free-standing building, the Great Temple. Unlike the hollowed-out caves in the cliffs surrounding the site, this complex stood on solid ground and covered an area more than twice the size of a football field. My guide, Suleiman Mohammad, points to a cloud of dust on one side of the temple, where I find Martha Sharp Joukowsky deep in a pit with a dozen workers. The Brown University archaeologist—known as “Dottora (doctor) Marta” to three generations of Bedouin workers—has spent the past 15 years excavating and partially restoring the Great Temple complex. Constructed during the first century B.C. and the first century A.D., it included a 600-seat theater, a triple colonnade, an enormous paved courtyard and vaulted rooms underneath. Artifacts found at the site—from tiny Nabatean coins to chunks of statues—number in the hundreds of thousands.

As I climb down into the trench, it feels as if I’m entering a battlefield. Amid the heat and the dust, Joukowsky is commanding the excavators like a general, an impression reinforced by her khaki clothes and the gold insignias on the bill of her baseball cap. “Yalla, yalla!” she yells happily at the Bedouin workers in dig-Arabic. “Get to work, get to work!” This is Joukowsky’s last season—at age 70, she’s preparing to retire—and she has no time to waste. They’ve just stumbled on a bathing area built in the second and third centuries a.d., and the discovery is complicating her plans to wrap up the season’s research. A worker hands her a piece of Roman glass and a tiny pottery rosette. She pauses to admire them, sets them aside for cataloging, then continues barking at the diggers as they pass rubber buckets filled with dirt out of the trench. It is nearing midafternoon, the sun is scorching, the dust choking and the workday almost over. “I wanted to finish this two days ago, but I’m still stuck in this mess,” Joukowsky says in mock exasperation, pointing to dark piles of cinders from wood and other fuel burned to heat the bath water of Petra’s elite. “I’m ending my career in a heap of ash.”

|

| A church used until the seventh century A.D. and excavated in the 1990s (Lamb Medallion from Byzantine floor mosai) contained papyrus scrolls that attest to Petra’s longevity. Lindsay Hebberd / Corbis |

Earlier archaeologists considered the Great Temple an unsalvageable pile of stones, but Joukowsky proved otherwise by attacking the project with a vigor she likely inherited from her parents. Her father, a Unitarian minister, and mother, a social worker, left Massachusetts to spend the years before, during and after World War II rescuing and resettling thousands of Jews and anti-Nazi dissidents. When the Gestapo shut down their operation in Prague, the couple barely escaped arrest. While they moved through war-ravaged Europe, their young daughter Martha lived with friends in the United States. Even after the war, her parents remained committed social activists. “They would be in Darfur were they here now,” Joukowsky says. “Maybe as a result, I chose to concentrate on the past—I really find more comfort in the past than in the present.”

She took up archaeology with gusto, working for three decades at various sites in the Near East and publishing the widely-used A Complete Manual of Field Archaeology, among other books. But Petra is her most ambitious project. Beginning in the early 1990s, she assembled a loyal team of Bedouin, students from Brown and donors from around the world and orchestrated the Herculean task of carefully mapping the site, raising fallen columns and walls and preserving the ancient culture’s artifacts.

When she began her work, Petra was little more than an exotic tourist destination in a country too poor to finance excavations. Archaeologists had largely ignored the site—on the fringe of the Roman Empire—and only 2 percent of the ancient city had been uncovered. Since then, Joukowsky’s team, along with a Swiss team and another American effort, have laid bare what once was the political, religious and social heart of the metropolis, putting to rest forever the idea that this was merely a city of tombs.

|

| One of the few entryways into Petra is a narrow passage, the Siq, at the end of which Petrans carved elaborate monuments into the soft rock. – Lonely Planet Images |

No one knows where the Nabateans came from. Around 400 B.C., the Arab tribe swept into the mountainous region nestled between the Sinai and Arabian peninsulas and the Mediterranean Sea. At first, they lived simple nomadic lives, eking out a living with flocks of sheep and goats and perhaps small-scale agriculture. They left little for future archaeologists—not even broken pottery.

The Nabateans developed a writing system—ultimately the basis of written Arabic—though the inscriptions they left in Petra and elsewhere are mostly names of people and places and are not particularly revealing of their beliefs, history or daily lives. Scholars have had to use Greek and Roman sources to fill in the picture. Greeks in the decades after Alexander the Great’s death in 323 B.C. complained about Nabateans plundering ships and camel caravans. Scholars believe that such raids whetted the Nabateans’ appetite for wealth. Eventually, instead of attacking caravans, the raiders began guarding them—for a price. By the second century B.C., Nabateans dominated the incense trade from southern Arabia. Within several decades, they had assembled a mercantile empire stretching for hundreds of miles. The people who a few generations earlier had been nomads were now producing eggshell-thin pottery, among the finest in the ancient world, as well as grand architecture.

By 100 B.C., the tribe had a king, vast wealth and a rapidly expanding capital city. Camels lumbered into Petra with boxes of frankincense and myrrh from Oman, sacks of spices from India and bolts of cloth from Syria. Such wealth would have attracted raiders, but Petra’s mountains and high walls protected the traders once they arrived in the city. The Siq, a twisting 1,000-yard-long canyon that in places is just wide enough for two camels to pass, made the eastern part of the city impregnable. Today it serves as Petra’s main entryway. It may be the most dramatic entrance to an urban space ever devised. In ancient times, though, the primary entrance into Petra was likely the road by which I came by donkey.

Writing early in the first century A.D., the Greek historian Strabo reported that while foreigners in Petra are “frequently engaged in litigation,” the locals “had never any dispute among themselves, and lived together in perfect harmony.” Dubious as that may sound, we do know that the Nabateans were unusual in the ancient world for their abhorrence of slavery, for the prominent role women played in political life and for an egalitarian approach to governing. Joukowsky suggests that the large theater in the Great Temple that she partially restored may have been used for council meetings accommodating hundreds of citizens.

Strabo, however, scorns the Nabateans as poor soldiers and as “hucksters and merchants” who are “fond of accumulating property” through the trade of gold, silver, incense, brass, iron, saffron, sculpture, paintings and purple garments. And they took their prosperity seriously: he notes that those merchants whose income dropped may have been fined by the government. All that wealth eventually caught the attention of Rome, a major consumer of incense for religious rites and spices for medicinal purposes and food preparation. Rome annexed Nabatea in A.D. 106, apparently without a fight.

In its prime, Petra was one of the most lavish cities in history—more Las Vegas than Athens. Accustomed to tents, the early Nabateans had no significant building traditions, so with their sudden disposable income they drew on styles ranging from Greek to Egyptian to Mesopotamian to Indian—hence the columns at the Great Temple topped with Asian elephant heads. “They borrowed from everybody,” says Christopher A. Tuttle, a Brown graduate student working with Joukowsky.

One of Petra’s mysteries is why the Nabateans plowed so much of their wealth into carving their remarkable facades and caves, which lasted long after the city’s free-standing buildings collapsed from earthquakes and neglect. The soft stone cliffs made it possible to hollow out caves and sculpt elaborate porticoes, which the Nabateans painted, presumably in garish colors. Some caves, Tuttle says, were tombs—more than 800 have been identified—and others were places for family members to gather periodically for a meal memorializing the dead; still others were used for escaping the summer’s heat.

At its peak, Petra’s population was about 30,000, an astonishing density made possible in the arid climate by clever engineering. Petrans carved channels through solid rock, gathering winter rains into hundreds of vast cisterns for use in the dry summers. Many are still used today by the Bedouin. Tuttle leads me up the hill above the temple and points out one such cistern, a massive hand-hewn affair that could hold a small beach cottage. Channels dug into the rock on either side of the canyon, then covered with stone, sent water hurtling to cisterns near the center of town. “There are abundant springs of water both for domestic purposes and for watering gardens,” Strabo wrote circa A.D. 22. Steep hillsides were converted to terraced vineyards, and irrigated orchards provided fresh fruits, probably pomegranates, figs and dates.

|

| Traders from Egypt and Greece traveled the city’s main road, once spectacularly colonnaded. – Gil Giuglio / Hemis / Corbis |

The pricier real estate was on the hill behind the temple, well above the hubbub of the main thoroughfare and with sweeping views to the north and south. Tuttle points out piles of rubble that once were free-standing houses, shops and neighborhood temples. A Swiss team recently uncovered, near the crest, an impressive Roman-style villa complete with an elaborate bath, an olive press and frescoes in the style of Pompeii. At the base of the hill, adjacent to the Great Temple, Leigh-Ann Bedal, a former student of Joukowsky’s now at Pennsylvania State University in Erie, uncovered the remains of a large garden. Complete with pools, shade trees, bridges and a lavish pavilion, the lush space—possibly a public park—is thought to have been unique in the southern part of the Middle East. It resembles the private ornamental gardens built to the north in Judea by Herod the Great, who lived until 4 B.C. Herod’s mother, in fact, was Nabatean, and he spent his early years in Petra.

By the fourth century A.D., Petra was entering its decline. Joukowsky takes me on a tour of the newfound spa, which includes marble-lined walls and floors, lead pipes and odd-shaped stalls that might have been toilets, all indications of prosperity. But the growing sea trade to the south had sucked away business, while rival caravan cities to the north such as Palmyra challenged Petra’s dominance by land. Then, on May 19, A.D. 363, a massive earthquake and a powerful aftershock rumbled through the area. A Jerusalem bishop noted in a letter that “nearly half” of Petra was destroyed by the seismic shock.

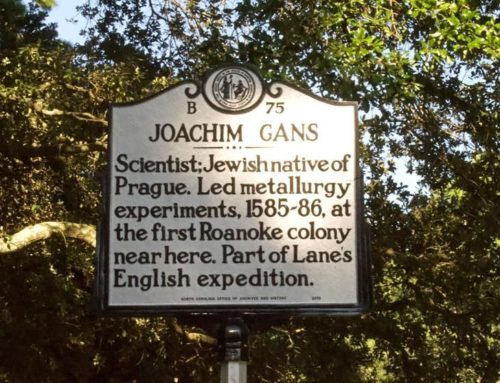

Scholars long assumed the catastrophe marked the end of the city, but archaeologists have found abundant evidence that Petra remained inhabited, and even prospered, for another three centuries or so. Almost 100 years after the earthquake, local Christians built a basilica now famed for its beautiful and intact mosaics of animals—including the camel, which made Petra’s wealth possible—just across the main street from the Great Temple. Some 150 scrolls—discovered when the church was excavated in 1993—reveal a vibrant community well into the seventh century A.D., after which the church and, apparently, most of the city was finally abandoned.

Forgotten for a millennium in its desert fastness, Petra reemerged in the 19th century as an exotic destination for Western travelers. The first, Swiss adventurer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, visited in 1812 when it was still dangerous to be a foreign Christian deep within the Ottoman Empire. Disguised as a Persian pilgrim, he marveled at Petra’s wonders but could not linger, since his curiosity aroused the suspicions of his local guides. “Great must have been the opulence of a city which could dedicate such monuments to the memory of its rulers,” he wrote. “Future travelers may visit the spot under the protection of an armed force; the inhabitants will become more accustomed to the researches of strangers, and then antiquities…will then be found to rank among the most curious remains of ancient art.”

Petra has lately fulfilled that prophesy. It is now Jordan’s top tourist destination, attracting hundreds of thousands of visitors a year. Hollywood’s Indiana Jones sought the Holy Grail in one of Petra’s caves in a 1989 film, dramatizing the site for a worldwide audience. The 1994 peace treaty between Jordan and Israel made mass tourism possible. Foreigners began coming to Petra, and devout Jews began making pilgrimages to nearby Jebel Haroun, which, according to tradition, is the site of the prophet Aaron’s tomb. The nearby village of Wadi Musa has been transformed from a straggling collection of run-down mud-brick houses into a boomtown of hotels (the Cleopetra) and stores (the Indiana Jones Gift Shop). Petra is also a top contender in an international contest to name the New Seven Wonders of the World. Candidates were nominated by a panel of experts, and winners will be chosen by votes. (You can vote online at new7wonders.com.) Winners are scheduled to be announced next month.

Despite all the publicity and the parade of tourists, much of Petra remains untouched by archaeologists, hidden under thick layers of debris and sand built up over the centuries. No one has found the sites of the busy marketplaces that must have dotted Petra. And although local inscriptions indicate that the Nabateans worshiped a main god, sometimes called Dushara, and a main goddess, the Nabateans’ religion otherwise remains mysterious.

So while the work by Joukowsky’s team has revealed much about ancient Petra, it will be up to a new generation of researchers like Tuttle to tackle the many rubble piles—and mysteries—that still dot the city’s landscape. “We really know next to nothing about the Nabateans,” says Tuttle as he surveys the forbidding landscape. “I hope to spend most of my professional life here.”

Tuttle and his colleagues will be assisted by Bedouin skilled in uncovering and reassembling the past. Bedouins lived in Nabatean caves for at least a century, until the 1980s when the government pressured most to move to a concrete settlement outside the ancient city to make way for visitors who come to explore the site. My guide, Suleiman Mohammad—who worked at the Great Temple before switching to the more lucrative tourist trade and who married a Swiss tourist—tells me he is grateful to have so many foreign visitors. But not all Bedouin are so lucky, he says. In the harsh country outside Petra, he points to a group far out in the desert: “They have no shoes, wear tattered clothes, and just have goats—there are no tourists out there!”

Suleiman invited the excavation team and me to dinner at his home that night. He greeted us warmly, and we climbed to the roof to enjoy the sunset. The red sun softens the ugly concrete village. Returning downstairs, we sat on cushions and ate from a large platter of traditional maglouba, clumping the rice into lumps with our hands and relishing the warm chicken. It was Thursday night, the start of the Arab weekend, and after dinner a young American and a Bedouin arm-wrestled to great laughter and shouting. Outside, the large waning moon rose and, far below, the red rock of Petra turned to silver in the soft desert night.

Andrew Lawler wrote about the archaeology of Alexandria in the April issue of Smithsonian. He avoids riding camels.