As major Afghan cities fall, the insurgents now oversee tens of thousands of artifacts and ancient sites.

By Andrew Lawler

Photographs by Robert Nickelsberg

As Alexander the Great did in 330 B.C., Taliban forces this week conquered the strategic cities of Herat and Kandahar while also taking a dozen other major towns across Afghanistan. The sudden victories caught the nation’s museum curators and archaeologists off guard, and they are scrambling to secure sites and artifacts still under their control. The fate of those within Taliban-run territory remains uncertain.

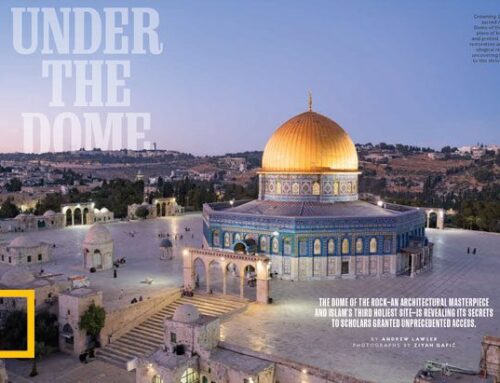

Taliban forces ransacked the National Museum of Afghanistan in early 2001, smashing images such as this Buddha head held by a curator.

“We didn’t expect this to happen so quickly,” said Noor Agha Noori, who leads Afghanistan’s Institute of Archaeology in Kabul. Officials intended to transport artifacts from cities like Herat and Kandahar for safekeeping, but the abrupt collapse of Afghan government resistance in recent days prevented those actions.

Now, with Taliban forces closing in on Kabul, the collection of more than 80,000 artifacts in Afghanistan’s National Museum is vulnerable. “We have great concerns for the safety of our staff and collections,” said Mohammad Fahim Rahimi, the museum’s director.

As an important crossroads for millennia, Afghanistan has an unusually rich heritage. Here, Buddhism spread to China, while Zoroastrianism, Christianity, Judaism, and Hinduism flourished before and after the arrival of Islam in the seventh century A.D. As a major artery on the Silk Road connecting India with Iran and China, Afghanistan is strung with remains of ancient cities, monasteries, and caravanserais that housed travelers—including Marco Polo on his way to the glittering court of Kublai Khan.

The Taliban, however, espouse a fundamentalist version of Islam that rejects all images of humans and animals and looks askance at the pre-Islamic past. Cultural heritage officials are divided over whether the group will again go on a rampage as it did in 2001, when it destroyed the famed Bamiyan buddhas as well as a host of objects and statues in the Kabul museum. (The freedoms Afghans have gained since 2001 are in jeopardy.)

In a February statement, Taliban leaders instructed their followers to “robustly protect, monitor and preserve” relics, halt illegal digs, and safeguard “all historic sites.” Significantly, they added that they would forbid selling artifacts on the art market.

Towering over the ancient city of Herat, the citadel that has served as fort, palace, treasury, prison, arsenal, and museum is now in the hands of Taliban forces.

But many Afghan cultural heritage experts are skeptical. “They have whitewashed their image, but they are still a very ideological and radical group,” said Omar Sharifi, a social science professor at the American University of Afghanistan. He fled Kabul for Delhi yesterday, saying he had received direct threats from Taliban members. Other Afghan sources added that cultural heritage staff across the country have received texts and phone calls from Taliban officials accusing them of working with international organizations.

Noori and Rahimi said that they have been in contact with their staffs in Taliban-controlled cities, and that these people appear to be safe. Lower-level employees have been told by Taliban officials that they will continue in their jobs. Since these employees have been confined to their homes, however, they have no information about the status of archaeological sites, museums, and artifacts.

“If they have bad intentions, it will become obvious down the road,” said Cheryl Benard, who directs the Alliance for the Restoration of Cultural Heritage (ARCH) based in Washington, D.C. “They are dealing with issues of borders and infrastructure now.”

Meanwhile, Kabul curators are speeding up efforts to export objects to a scheduled museum exhibit in Paris. Philippe Marquis, director of the French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan, hopes to return to Kabul shortly to oversee packing of the Paris-bound artifacts. “The situation is very unpredictable,” he said. “People in Kabul have a terrible fear of the Taliban. But a quick war with few casualties could be better than anarchy.”

Afghan officials declined to specify what plans they have for the National Museum’s world-famous collection. “We need to safeguard the artifacts, but the question is how to find a safe location,” one government source said. “There is no way for them, or the staffs, to leave the country.” Another added that he is confident the United Nations will put pressure on the Taliban to protect both cultural heritage officials as well as artifacts and ancient sites.

The Taliban already is in full control of Mes Aynak, one of Central Asia’s great ancient Buddhist monasteries located just outside the capital. Along with the myriad stupas and statues are a total of 10,000 artifacts excavated from the site, including more than 2,500 coins. The group also now oversees the new museum in the Herat citadel, as well as smaller museums and collections in Kandahar, Ghazni, and Balkh.

Meanwhile, those in Kabul await an uncertain future. “The Taliban know me, and it’s not a comfortable thought for me and my family,” said one cultural heritage expert, who added that the city’s parks and sidewalks are filled with refugees. “But there are no visas to be had.”

Andrew Lawler is a journalist and author who has written about controversial excavations under Jerusalem for National Geographic. His latest book, Under Jerusalem, will be published in November.

Robert Nickelsberg worked as a Time magazine contract photographer for nearly 30 years, specializing in political and cultural change in developing countries. He is the author of Afghanistan – A Distant War, published in 2013 by Prestel, which represents his 25 years of work in Afghanistan. Nickelsberg’s latest book, Afghanistan’s Heritage: Restoring Spirit and Stone, done in conjunction with the U.S. Department of State, was published in English, Dari, and Pashtu in May 2018.