The Roanoke settlers laid the foundation for the British colonies. Without those mysteriously disappearing colonists, we might not have America.

It’s the Fourth of July, the perfect time to reconsider just who sparked the 13 Colonies that launched our United States. No — it wasn’t the English who arrived in 1607 at Jamestown or the Puritans who landed at Plymouth in 1620. The real originators of the country were members of an obscure band of Elizabethans who settled on the Outer Banks of North Carolina a generation before their more famous successors.

Yeah, the same ones highlighted in FX’s “American Horror Story: Roanoke,” the settlers who vanished without a trace in 1587 — those 115 men, women and children who disappeared on remote Roanoke Island provide an irresistible tale for Hollywood producers.

But archaeologists and historians have begun to see Roanoke as America’s creation story. Without the model set by the Roanoke voyages, some scholars now say, it is hard to imagine a Jamestown, a Plymouth, 13 Colonies or even the United States. “The profound significance of (Walter) Raleigh’s Virginia voyages to the history and culture of the modern world is often forgotten or undervalued,” writes Neil MacGregor, an art historian and former director of the British Museum.

Had the English not made their failed 1580s push to settle North America, other Colonial powers likely would have expanded their reach into what are now the mid-Atlantic states.

Roanoke’s history

Organized by the queen’s principal security guard, Walter Raleigh, the Roanoke enterprise aimed to exploit New World resources and rival Spanish shipping. Raleigh drummed up investors and sent soldiers, merchants and scientists to Roanoke in 1585. The poorly supplied settlers quickly went hungry and were soon at odds with the Carolina Algonquians. After assassinating the local Native American leader, they fled back to England.

The English settlement might have ended with their hurried departure. But a group led by the expedition artist, John White, persuaded Raleigh to use a newfangled approach called a corporation to try again. The colony would include families and single women, as well as men. They set off in 1587 with White as their governor.

He returned to England that summer for supplies and additional settlers just as war with Spain broke out. He couldn’t get back to Roanoke until 1590, when he found a deserted settlement with only the word “Croatoan” carved in a tree. White believed that the settlers had moved to Croatoan, an island only 50 miles to the south of Roanoke. But a sudden storm forced him back to sea, and he never returned to the Americas. The Colonists vanished and slipped into obscurity.

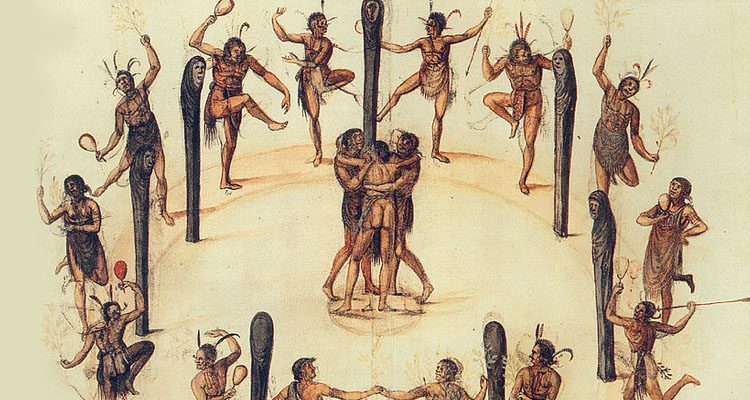

Recent excavations suggest that the Colonists threw in their lot with the Indians. While they didn’t succeed in establishing a permanent English settlement, the venture generated highly accurate maps, detailed lists of resources and remarkable watercolors by White that shaped the way the Europeans saw the indigenous people of North America.

It was this material that reignited English interest in the New World when Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603 and war with Spain ended. The Roanoke venture forged the first link in the chain binding England with North America; Jamestown and Plymouth were mere sequels.

Today, academics have begun to appreciate the Roanoke venture as more than a perennial source of kitschy horror stories or conspiracy theories. On Independence Day, take a moment when lighting that bottle rocket to remember the lost Roanoke settlers who founded our country.